Influence of Islamic Architecture on Residential Structures in the Hausa Community

Influence of Islamic Architecture on Residential Structures in the Hausa Community

Aisha Abdulkarim Aliyu*

Department of Architecture, University Technology Malaysia

Department of Architectural Technology, Jigawa State Polytechnic Dutse, Nigeria

Alice Sabrina Ismail

Department of Architecture, University Technology Malaysia

*Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Aisha Abdulkarim Aliyu, Department of Architecture, University Technology Malaysia, and Department of Architectural Technology, Jigawa State Polytechnic Dutse, Nigeria at [email protected]

Abstract

The architectural traditions of Islamic cultures have been influenced by Islamic teachings historically. These teachings include values, such as discretion, modesty, and hospitality. These values work as guiding principles and impact the construction of Muslim houses, arrangement of spaces, and interaction of people with one another. However, the current political and social shifts, together with the ideas departing from Islamic cultural values are rather upsetting for Muslims. Resultantly, some of the architectural styles have emerged that go against the ideals and principles, upheld by Islamic beliefs. The current study, in connection with the influence of Islamic cultural values, attempted to examine the shape, traits, and components of housing, thoroughly. Moreover, it also focused on the interactions between these elements in different Islamic towns with different environmental conditions as well. Two case studies were conducted in the Kano metropolitan region by employing a qualitative methodology. This methodology comprised document analysis and direct observation presented within the context of interpretivist research paradigm. The findings showed that religious beliefs form the basis of regional design, with Islamic civilizations' architectural works deriving their inspiration directly from the Islamic principles. The academics underlined the significance to understand Islamic beliefs and values while taking into account the evolving conditions surrounding the contemporary designs in light of the research findings. This knowledge is essential to properly articulate the local Islamic identity in a way that responds to the demands of contemporary society.

Keywords: Hausa community, housing architecture, Islamic values, Islamic ideas

Introduction

The architectural design within the realm of Islamic architecture exhibits a consistent adherence to Islamic principles across different times and regions, yet it is manifested in varying forms. [1] Islamic architecture takes into account the environmental considerations and develops a distinct architectural philosophy for different types of structures.[2] In this examination, architecture was viewed through the prism of Islamic ideals rather than solely studying the Islamic architecture in isolation.[3] Establishing the Islamic principles and designing the guidelines that respect these goals while taking into account contemporary demands was the major aim.[4] The Islamic laws, beliefs, and traditions impacted the Hausa society’s-built environment, significantly. Islamic architectural design aims to establish a harmonic balance between family privacy and social togetherness by carefully planning the transitions between private and public spaces.[5]

Islamic houses are specifically designed to meet the varied demands of the families, taking into account certain factors, for instance, lifestyle, comfort, culture, geography, economics, building materials, and other pertinent considerations.[6] The needs, social standing, and personalities of the household members have a significant impact on its design.[7] Buildings should be constructed in such a way that supports and improves their intended uses. In Islamic architecture, the usefulness and practicality are provided more weight than aesthetics.[8] The Holy Qur’ān[9] describes an ideal Muslim family as one that practises hospitality, kindness, and the provision of basic requirements, for instance, food and clothing. It also mentions the practise to share meals as one of these characteristics.[10] Throughout the day and night, when people enter and leave their residences, one can hear the exchange of peaceful greetings, known as Salaam.[11] Islam continually encourages interpersonal relationships by developing strong connections, especially with family and neighbours, since these gestures help to nurture love, generosity, and compassion. According to the Holy Qur'ān, "And We have made between you affection and tenderness," therefore such connections are highly recommended.[12]

Islam has developed moral guidelines that dictate how people should behave towards one another as well as their way of life and manners.[13] As symbolic symbols of the sanctity and isolation, ingrained in the Islamic concept of a house, the shape, qualities, and interaction of these aspects within dwellings are all important.[14] In order to comprehend the evolution of housing in a specific geographical area, it is essential to conduct research on the corresponding society.[15] Due to their divergent change trajectories, different cultures cannot fulfil their urban needs in the same way.[16] The traditional Middle-Eastern and African building practises lay a strong emphasis on religious principles, interpersonal relationships, and neighbourly interactions, with particular attention to respect the neighbourly rights and follow religious precepts.[17]

2. Literature Review

2.1 Effect of Islamic Concepts on Architecture in Islamic Societies

The peculiarity of Islamic architectural forms and the consistency of the underlying concepts serve as evidence that Islamic architectural practises are deeply based on Islamic conceptions.[18] The Islamic faith is the earliest and primary of these conceptions, acting as a trustworthy and enduring source of cultural concepts and architectural ideals.[19] The architectural traditions of Islamic countries are influenced by this concept.[20] The second factor is the current context, which includes many characteristics of culture, climate, society, politics, and economy.[21] Resultantly, the architectural styles used in Islamic nations vary according to regional settings and their adherence to the Islamic faith.[22]

2.1.1. Islamic Architecture as Cultural Unity

Architectural changes are a reflection of intellectual and cultural advancements due to major influence that cultural changes have on architectural and aesthetic trends.[23] Architecture, at its core, is a cultural artefact that serves as a manifestation of a community's prevailing culture and social ideals.[24] Numerous architectural designs have been shaped by the prevailing zeitgeist, often without explicitly referencing a specific cultural identity.[25] This is due, in part, to the waning influence of local designs brought about by the pervasive impact of Western cultural influences.[26]

2.1.2. Social Variables and the Transformation of Architectural Concepts

The progress in politics, society, and technology has enabled the European nations to exert a greater control on the developing countries, leading to an imbalanced relationship between these nations and their development, as well as the prevalence of Eurocentric architectural principles.[27] Western architectural schools, seeking to establish a basis for building designs, embraced concepts that reflected the materialistic values of the Industrial Revolution.[28] At the same time, there was a tendency to simplify the architectural shapes and components.[29] This trend was furthered by the Industrial Revolution, which brought about new building materials that needed effective production and mechanised manufacturing techniques.[30]

2.1.3. Shifts in Islamic Concepts

Prior to the influence of economic and technological advancements that transformed the social and civic life, Islamic countries were predominantly shaped by religious concepts and beliefs.[31] The Islamic architectural styles reflected Islamic society's ideals and goals.[32] The advent of renaissance and the development of new building materials, however, presented problems that could not be solved by using conventional knowledge merely.[33] In response, local Muslim architecture started embracing practical aesthetic concepts and ideas from various disciplines, such as science and art.[34] Consequently, it started incorporating the elements of Western architectural vocabulary. Architecture, as a profession, transcends the international boundaries and operates on a global scale[35]

2.1.4. Characteristics of Muslim Residences

An Islamic residence encompasses several vital elements including the principle of women seclusion and privacy5. The term "Sakinah," which translates to "calm and sacred," holds significant value in Islamic architecture and should be integrated while designing the houses to enhance the occupants' sense of security and comfort.[36] Moreover, the design should prioritize qualities, such as orderliness, simplicity, cleanliness, modesty, and pleasant odours.[37] Consequently, Islamic residential architecture should incorporate the principles of universal design, ensuring inclusivity and accessibility for all individuals.[38] Specifically, the Islamic architectural principles emphasize the value of seclusion for Muslim residents.[39] The arrangement and configuration of the house's interior layout, including the positioning of doors, play a crucial role in determining the level of privacy afforded.[40] Islam significantly emphasizes to safeguard human privacy, particularly when it comes to preserving the modesty and integrity of women's "auras" (private parts). “If ye find no one in the house and enter not until permission is given to you: if ye are asked to go back, go back: that makes for greater purity for yourselves, and God knows well all that ye do.”[41]

Two key components are considered important when it comes to privacy, that is, visual and acoustical privacy.[42] Visual privacy entails considerations regarding the design of openings in the house, such as doors and windows, their height, and the degree of shielding they provide to maintain the privacy of female occupants.[43] The site and floor plan are two key components that fall within this category.[44] On the other hand, acoustic privacy is a crucial aspect of a home that should be taken into account in order to prevent the transmission of sound from one dwelling to the outside environment, as well as from private spaces to public areas.[45] Maintaining acoustic privacy helps to ensure a peaceful and secluded atmosphere within the home.[46]

2.2 Islamic Perception of House Design

Islamic teachings, encompassing the Holy Qur'ān, Sunnah, and Sharī‘ah, emphasize a strategic approach to all aspects of life.[47] Muslims use the Holy Qur'ān and the example of the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) in their organisations and management of their activities in a variety of sectors including social, economic, and personal spheres.[48] This cultural emphasis encourages the comprehensive planning and design of houses from every perspective.[49] As the most prominent typology, Islamic architecture has evolved as a holistic code for the design and construction of various buildings.[50] It facilitates the daily practice of religion and supports the notion that the layout of a home should cater to the needs and desires of its inhabitants.[51] In fact, Ibn Qutayba, a renowned Muslim philosopher from the ninth century, likened the suitability of a home to the perfect fit of a shirt for its wearer, highlighting the importance of a home being tailored to its residents5. This provides concrete evidence of the significance placed on a home's suitability for its occupants.[52] In Islamic architecture, forms and functions serve as the basis for both aesthetic and practical considerations3.

Table 1. Design Features of Islamic Housing

|

Design Feature

|

Graphical Presentation

|

Comments

|

|

1. Entrance

|

|

Entryway is dipped to make it easier for visitors to enter the house privately1 .

|

|

2. Gender based

Spatial

organization

|

; |

Islam places a high priority on privacy. House encourages gender-based spatial organisation 24.

|

|

3. Inward Looking

|

|

The direction of residential spaces is inward-looking [53].

|

|

4. Minimal Design of Façade

|

|

To convey modesty, the façade uses a straightforward strategy and the bare minimum of design elements 16.

|

|

5. Placement of

Toilet

|

|

Given that it is forbidden to face the Qibla while using the toilet, the positioning of the toilet in a home is a sensitive matter 5.

|

2.7 Housing Practices in Different Ethnicities

Individuals grouped along family lines are born, nurtured, and schooled in houses, which serve as microcosms of their respective cultures and civilizations.[54] Muslims from different ethnic groups in Nigeria have developed their own residential architecture in recent years.[55] With the help of Islamic teachings, local climatic factors, and a variety of construction methods, a typology of traditional homes in their homelands has been constructed.[56] The three main ethnic groups' home designs with a focus on the Hausa people have been discussed below:[57]

Figure 1. Map of Nigeria Showing the Three Ethnic Groups.[58]

2.8 Western (Yoruba Community)

The traditional buildings of Yoruba and Benin civilizations define the architectural forms common in Western Nigeria.[59] The use of building materials, courtyards, and impluvia are some examples of commonalities between the Yoruba and Benin dwelling styles.[60] Notably, the architecture of homes in this area frequently has a rectilinear shape, with a courtyard for each family.[61] Two sorts of Yoruba traditional compounds were essentially discovered. The first form consists of compounds built around a central hall or corridor that house several polygamous families connected by senior male members through agnatic relationships. Based on a group of adult males whose shared agnatic lineage shapes their internal organisation and moral unity, each compound has a tendency to display a similar basic form and structure.[62]

2.9 Eastern (Igbo Community)

There are a number of distinctive architectural features in Nigeria's Eastern region, which is primarily inhabited by the Igbo tribe.[63] These include the presence of verandas in front of every residence, rectangular homes that frequently have no windows, and the frequent usage of forked posts to support roofs. The common Igbo architectural characteristics were also noted by,[64] featuring enormous compound gates, gathering places, shrines, and two-to-three-story semi-defensive Obuna Enu structures. Typically, a fence surrounds each compound, with only one access and exit. Igbo buildings' roofs are expertly made with palm ribs and grasses that are also ornamental in and of themselves.[65] The impluvia, a central open area in the complexes that gathers rainwater, is surrounded by several rooms, storage spaces, and a kitchen.[66] While, the children's quarters are typically clustered together, it is normal for the men's portions to be divided from the women's and children's sections.[67] Mud, hardwood lumber, palm fronds, midribs, bush twines, and pawpaw trunks are traditional building materials used in Igbo architecture. These materials are utilised to build drainage systems for the impluvium.[68]

2.10. Layout Plan of Hausa Traditional Community

A well-designed floor plan plays a crucial role in preserving the privacy within a person's home and careful consideration is given to the arrangement of public and private rooms.[69] Muslim homes typically have a public area where guests and visitors are welcomed. However, precautions should be taken to protect the privacy of the residents.[70] One effective way to achieve this is by establishing indirect sight paths between the guest area and the family space.[71] Areas, such as living room and kitchen, where women are often present, also require special attention to maintain privacy.[72] The layout of a typical Hausa residence is quite similar to the "Sudanese" architectural design, common in the West African savannah regions, especially the Niger and Chad river basin.[73] The homes in Hausa culture are distinguished by courtyard designs, surrounded by several rooms, allowing the families to grow including wives and children.[74] The concept of planning also includes designated spaces outside for various activities.[75] Islamic design principles emphasize the importance to provide women with solitude and seclusion. Resultantly, Hausa compounds are separated into two parts namely the front part, known as the "Zaure," which belongs to the owner of home and the back part which is beyond the "Zaure," used by women and is built around a courtyard.[76] According to Islamic rules, this division ensures that women in purdah are kept apart from the exterior male reception area.[77]

In order to express ideas of authority, religion, and visual arts, royals and wealthiest urban residents constructed vast complexes with towering structures and artistically decorated façades as part of the Hausa society's larger cultural goal. The ostentatiousness of each compound functioned as an instantly recognizable barometer for its owners' social rank. Their compounds featured many structures, housing dozens of their extended families as well as staff and craftsmen. They made extensive use of a variety of architectural elements, such as vaulting, double-story construction, enormous domes, and open interiors and entrances. The Hausa masons and architects used locally accessible building materials, mainly palm wood and rammed earth, to construct the most impressive architectural marvels recorded in the medium. They constructed buildings that were suitable for the region's alternating humid and dry environment and fulfilled both functional and monumental functions. While preserving a fairly distinctive style, the Hausa masons benefited from the greater range of architectural designs and building techniques employed throughout cosmopolitan West Africa.

Indeed, the "Zaure" in Hausa architecture holds significant social and religious importance within the structure. According to,[78] it performs a variety of functions and acts as a symbol of the socio-religious group, demonstrating the degree of acceptance within the neighbourhood. Only recognised and honourable men are permitted to cross this threshold, highlighting the value of hierarchy and respect.[79] "Zaure" serves a number of purposes, such as creating a welcoming environment, assuring safety and protection, maintaining privacy, following moral principles, reflecting ethnic beliefs, acting as a decorative feature, and serving as an administrative space. It provides room for children's activities, enables the celebration of social events, for instance, marriages and naming ceremonies and acts as a venue for bigger meetings.[80] Due to its open layout, it encourages neighbourhood social interactions and the forging of ties between neighbours.

2.11 Segregation Between Public and Private Spaces in Hausa Community

The inner core, centre core, and outer core’s conceptual divisions of a typical Hausa home's layout represent the household's hierarchical structure and spatial segregation.[81] The ward, guest/servant area, and a backyard for activities like animal rearing and waste disposal all fall under women's area, which is in the centre of the building.[82] In Hausa architecture, the centre core, which mainly consists of a courtyard, fulfils a number of functions.[83] It acts as a hub for activity in the area, provides natural lighting and air, and is used for both household and social events.[84] It is where families carry out their daily home duties and engage in social or ceremonial activities.[85] The courtyard also provides a safe and peaceful environment for children to play and crawl without any disturbance. Additionally, it serves as a communal space where family members can gather, converse, share meals, and even sleep during hot and humid nights or seasons.[86] These design principles and significance of the courtyard as a central space in Hausa dwellings reflect the cultural and practical considerations of the community, fostering social interaction, comfort, and harmony within the household.[87]

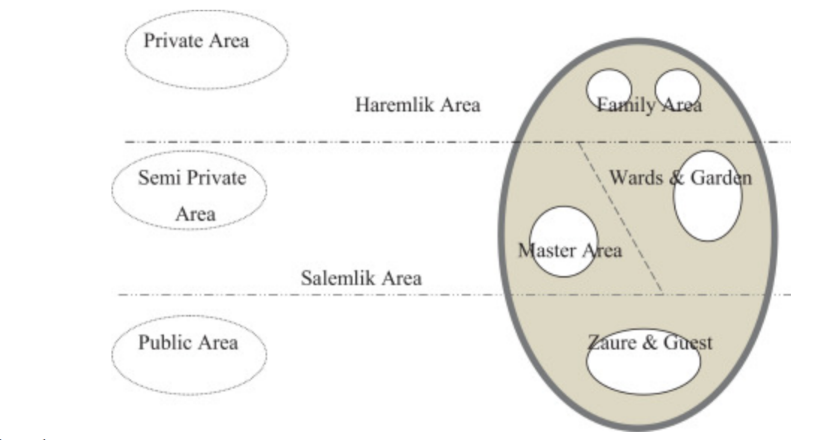

Figure 2. Typical Hausa Compound Segregation 32

In fact, Hausa culture's belief in "Purdah," or women's exclusion, profoundly impacts the architecture of their homes and is also mirrored in the architectural arrangement as well.[88] The concept of accessible and non-accessible spaces, referred to as Haremlik (women's quarters) and Selemlik (public area), creates a distinction between internal and external spaces within the compound.[89] This segregation aligns with the Islamic architectural principles that emphasize privacy and modesty.[90] In Hausa architecture, the courtyard system is still widely used as a place for social and household activity.[91] Additionally, the kitchen and dining areas are crucial, with the kitchen sometimes separated from the living spaces inside the property.[92] This division aids to maintain cleanliness and reduces the entrance of cooking odours.[93] Depending on the precise configuration, dining areas might be found either privately within each household or collectively in a parlour or open space.[94] Restrooms are often located away from the main living spaces or at the end of the complex due to hygienic and privacy concerns.[95] This placement ensures that they are separated from more communal spaces by providing a sense of privacy and convenience for the inhabitants.

Table 2. Traditional Hausa Elements

|

S/No.

|

Figure

|

Description

|

|

1.

|

|

Engravings

§ Since ancient times, detailed designs have been carved into wall surfaces by using the process of engraving which includes carving grooves into the surfaces.

§ The three types of decorative features used in Hausa traditional architecture include surface designs, calligraphy, and ornamental motifs.

|

|

2.

|

|

Arches

§ The use of arches in Hausa architecture is distinctive, particularly the construction of domed rooms by using intersecting arches that extend from the building's walls.

§ For the construction of these arches, palm wood is used, which is inserted into the walls and gradually angled until it becomes horizontal at the highest point of the arch.

|

|

3.

|

|

Pinnacles (Zankwaye)

§ The pinnacles, or Zankwaye, are yet another essential component of Hausa architecture.

§ Zankwaye, which originally resembles a bull's horns in their reinforced vertical projections surrounding the parapet wall of the roof, serves as a convenient route for contractors to access the roof while it was being built or repaired.

|

|

4.

|

|

Sprouts (Indararo)

§ The roof eaves (Indororo), which protrude from the palm-wood framework inside the roof, are another highlight.

§ These extended and protruding roof eaves and downspouts are used to drain rainwater off the roof and stop it from soaking into the structure or weighting it down.

|

|

5.

|

|

Dome

§ Hausa master masons created a range of structurally sound arch configurations to maximise the free-span of rectilinear buildings, despite the structural restrictions of the building materials. Domes are a significant element of Hausa architecture.

§ The Hausa vault and dome are based on a fundamentally different structural idea than the stone domes of North Africa that were inspired by the Romans.

|

|

6.

|

|

The windows (taga)

§ The Hausa homes were typically modest in size (nearly slit-like) and high on the outside walls of the residential complex.

§ This was perfect for the humid climate since it had mostly wooden shutters that let light in and allowed for a controlled air flow.

|

|

7.

|

|

Doorway

§ In Hausa structures, outer doorways were frequently covered with curtains, while inside doorways were closed by wooden or iron doors (kofa) that rotated a pivot.

§ In the design of the entryway, lintels, beams, brackets, and corbels were frequently used.

|

3. Methods

The current study utilized a qualitative approach, specifically document analysis and direct observation. The study followed interpretivist research paradigm, which focuses to understand the subjective meanings and interpretations of individuals. The purpose of the study was to determine how Islamic principles are applied to architecture in Nigeria's three major ethnic groups namely the Northern, Western, and Eastern areas. Moreover, the study also emphasized to investigate how these Islamic principles were historically put into effect while examining the characteristics of privacy in residential Hausa architecture, simultaneously. It also aimed to pinpoint the Islamic privacy principles and their representation in Hausa’s domestic architecture through the analysis of pertinent documents and first-hand observation of architectural specimens.

4. Findings

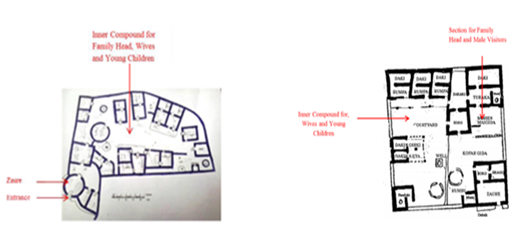

This section discusses the findings gathered from traditional Hausa housing plan. Islam has historically emphasized the rights of families residing in Islamic communities, particularly in conventional housing. The designs of Islamic dwellings' entrances, which are frequently twisted or followed by an inner space to obstruct the view from the outside, reflects the custom that forbids direct visualization of the house. Family members have access to internal spaces, however, the guests are not allowed there to prevent them from entering into the main house. It can be seen from samples A and B that the inner complex is primarily designed for women, while the outside area is created for men of the household, with a separate section for the Turaka, that is, the head of the household. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 5, the Zaure is primarily designed in traditional houses as the visitors’ waiting space. Typically, the kitchen is one-sided, as seen in Fig. 5 and is not joined to the sleeping space. Specific steps are followed in Islam to protect the family rights. While, the external apertures are tiny and elevated to promote privacy, the openings overlooking the interior courtyard are huge. The family room is a private space that may only be visited at certain times and cannot be entered without authorization. "Whoever believes in God and the day of judgement, does not harm his neighbors," the Prophet (SAW) remarked. Following measures were taken to preserve the neighbors’ rights. These measures proved to be effective: orienting the rooms toward courtyards as seen from samples A and B, which lowers the exterior openings, blocks the surrounding views, and provides privacy.

Figure 3. Sample A of Traditional Building Plan Figure 4. Sample B

Figure 5. Traditional Waiting Area (Zaure) Figure 6. Sample Traditional Kitchen

5. Modernity and Privacy in Hausa New Housing

The transformation of architectural features and planning principles within small neighborhood units, evolving from organic and spontaneous forms to geometric and grid-like layouts, significantly influences the dynamics of private and public spaces. This transition has implications not only for security and privacy, however, also for individuals' sense of identity and humanity. The shift from an introverted neighborhood concept, where buildings were socially, culturally, economically, and politically integrated and isolated complexes, to an extroverted one has reshaped the spatial dynamics. This shift has led to a transition from internal to external orientations, resulting in open and accessible entrances, as well as direct external views into interior communal spaces. Unfortunately, this shift has led to the removal of transitional areas that play a vital role in residents' daily lives, impacting the social, cultural, and structural aspects of new residential developments. These changes often disregard the Islamic values and cultural requirements of specific communities, such as Hausa, leading to design schemes that lack important cultural and social considerations.

Figure 7. Modern low-cost Housing.

Authors Field work 2023

Figure 8. Modern Low-cost Housing

Authors Fieldwork 2023

Table 3. Islamic Design features of Hausa Architecture.

|

Design Features

|

Image (Traditional)

|

Description

|

|

1. Simple Design

|

|

The design communicates Hausa community in most cases.32

|

|

2. Internal Space organization

|

|

The structure of the family home must clearly reflect the separation of men and women, as demanded by Islam.[96]

|

|

3. Inward-looking

|

|

The direction of residential spaces is inward-looking.54

|

|

4. Courtyard

|

|

To accommodate more wives and their children, houses are built around a courtyard, providing an outside area for women in purdah.[97]

|

|

5. Minimal Design of Façade

|

|

In general, Hausa buildings have smaller windows. The facade uses straightforward strategy and the bare minimum of design elements.49

|

6. Conclusion

Privacy is inevitably a key component in Islamic housing architecture and is deeply ingrained in Islamic cultural traditions. These cultures value privacy as a virtue, which is cleverly expressed through architectural choices including room layout, door placement, and fence design. Design is further influenced by gender segregation, resulting in separate spaces for men and women that promote modesty and privacy. It is crucial to distinguish between public and private spheres, designating visitor-friendly areas while reserving private spaces like bedrooms and prayer rooms for retreat. The seamless integration of a designated bathing space ensures modesty during hygiene procedures. The Islamic decoration, which includes calligraphy, geometry, and nature-inspired designs, not only reinforces the aesthetic appeal, however, also serves to represent spiritual ideas. Islamic design values, which encourage moderation, cleanliness, and simplicity of maintenance, are emphasised by responsible expenditure and good hygiene. The contemporary problem to balance religious beliefs with contemporary demands requires architects to integrate cultural and religious values with changing needs, harmonising local character with contemporary essence in housing designs.

7. Recommendations

The current study attempted to investigate the interaction of Islamic ideas with traditional and contemporary approaches. It also emphasized to divert the attention from interpreting the Islamic goals within a more complex social framework and from spatial necessities as the main impetus as well. This necessitates a thorough investigation, research, and assessment of neighbourhood units while taking socio-cultural factors into account. The neighbourhood depends on shared values among decision-makers and active participation from local customers. It is envisioned as a sanctuary defined by isolation, safety, community, and shared identity. By encouraging the communities, sensitive to privacy issues, architectural standards, and residential socio-spatial requirements, living situations can be improved. This method emerges as a crucial tactic for effective planning and Islamic compliant housing design.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Tertiary Education Trust fund (TETFUND) Scholarship and Universiti Technologi Malaysia's Fundamental research grant scheme (KPT) vot grant number (5F492) internal grant for paper publication support. The authors are responsible for the information provided, the claims made, and the opinions expressed.

Conflict of Interest

Author(s) declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Details

This research did not receive grant from any funding source or agency.

Bibliography

Abdelgalil, Reda Ibrahim Ibrahim Elsayed. "The Philosophy of Creativity, Innovation and Technology from an Islāmic Perspective." Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 13, no. 1 (Spring 2023). https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.131.16.

Adenaike, Folahan Anthony, Akunnaya Pearl Opoko, and K. G. Oladunjoye. "A Documentation Review of Yoruba Indigenous Architectural Morphology." International Journal of African and Asian Studies 66, no. 1 (July 2020): 27-31. https://doi.org/10.7176/JAAS.

Agboola, Oluwagbemiga Paul, and Modi Sule Zango. "Development of Traditional Architecture in Nigeria: A Case Study of Hausa house form." International Journal of African Society Cultures and Traditions 1, no. 1 (June 2014): 61-74.

Akhtar, Muhammad, Muhammad Atif Aslam Rao, and Doğan Kaplan. "Islamic Intellectualism versus Modernity: Attempts to Formulate Coherent Counter Narrative." Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 13, no. 1 (July 2023). https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.131.18.

Alhuseini, Majedh F., Ghadah A. Altammam, Bashayer R. AlSehaimi, Donia M. Bettaieb, Abeer A. Alawad, and Khawlah J. Tarim. "Conceptual Inspiration from Heritage: the Design Philosophy Surrounding the Saudi Arabian Rowshan." City, Territory and Architecture 10, no.1 (July 2023): 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-023-00204-6.

Aliyu, Mohammed, and J. A. Ahmed, "Questioning the Neo-Classical Residential Buildings of Kano Metropolitan City Within the Context of Hausa Traditional Architecture." Journal of Advanced Research in Construction and Urban Architecture 4, no. 3 (2019): 38-47.

Ali, Mohd Akil Muhamed, Mohd Farhan Md Ariffin, Mohd Nazri Ahmad, and Shafiza Safie. "Islamic Values in the Design of Residential Internal Layout." International Journal Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 12, no. 11 (November 2022): 1728 – 1740. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i11/15051

Aliyu., Aisha Abdulkarim. Abdullahi Sagir, Alice Sabrina Ismail, and Yakubu Aminu Dodo. "Considering Afrocentrism in Hausa Traditional Architecture." International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 7, no.11 (November 2022): 52-57.

Aliyu Mohammed, and Hussaini Haruna. "Architectural Revivalism: The Progressive Design Approach in Hausa Communities." International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications 7, no. 4 (December 2021): 143-149. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijaaa.20210704.16.

Alifuddin, Muhammad, Alhamuddin Alhamuddin, Andri Rosadi, and Eko Ariwidodo. "Understanding Islamic Dialectics in The Relationship with Local Culture in Buton Architecture Design." Karsa: Jurnal Sosial dan Budaya Keislaman 29, no. 1 (June 2021): 230-254. https://doi.org/10.19105/karsa.v29i1.3742

Auwalu, Faisal Koko. "Exploring the Different Vernacular Architecture in Nigeria." International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions 7, no.1 (February 2019):1-12.

Babangida Hamza, and Halima Sani-Katsina. "Integrating Islamic Design Principles for Achieving Family Privacy in Residential Architecture." Journal of Islamic Architecture 5, no. 1 (June 2018): 9-19.

Batagarawa Amina., and Tukur Rukayya Bashiru, Hausa Traditional Architecture in Sustainable Vernacular Architecture. Springer, Cham, March, 2019.

Bello, O., and B. Jolaoso. "Character-extinction of Yoruba Architecture: An Overview of Facades of Residential Buildings in South-Western, Nigeria." Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies 8, no. 3 (June 2017): 143-150. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-b391bd047.

Bello, Abdulqadir., and István Egresi. "Housing Conditions in Kano, Nigeria: A Qualitative Assessment of Adequacy." Analele Universitatii din Oradea, Seria Geografie no.2 (December 2017): 205-229.

Bokhari, A., M. Hammad, and D. J. A. M. E. L. Beggas. "Impact of Islamic Values and Concepts in Architecture: A Case Study of Islamic Communities." Proceedings of Sustainable Development and Planning XI, no.241 (2020): 9-11. https://doi.org/10.2495/SDP200311.

Bunge, Mario., and Taha Abd al-Rahman. Modernity and the Ideals of Arab-Islamic and Western-Scientific Philosophy. Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2023.

Danja, Isa Ibrahim., Xue Li, and S. G. Dalibi. "Vernacular Architecture of Northern Nigeria in the Light of Sustainability." In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 63, no. 1 (March 2017). https://doi.org/10.30822/arteks.v7i3.1966.

Danjuma, Aliyu Maiwada., Bilkisu Tahir Mukhtar, Ahmed Osman Ibrahim, Fatima Baba Ciroma, Kabir Umar Yabo, and Yakubu Aminu Dodo. "Examination of Hausa Cultural Identity in Architectural Design." PalArch's Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17, no. 9 (2020): 10122-10133.

Dmochowski, Z. R. "An Introduction to Nigerian Architecture-Northern Nigeria." Ethnographica Ltd, London. 1 no. 1 (1990): 1-2.

Fan, Zi-Mu., Bo-Wei Zhu, Lei Xiong, Sun-Weng Huang, and Gwo-Hshiung Tzeng. "Urban Design Strategies Fostering Creative Workers' Sense of Identity in Creative and Cultural Districts in East Asia: An Integrated Knowledge-Driven Approach." Cities 137 (June 2023): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104269.

Folkers, Antoni S., and Belinda AC Van Buiten. Modern architecture in Africa: Practical Encounters with Intricate African modernity. Springer, 2019.

Gharipour, Mohammad, and Daniel E. Coslett, eds. Islamic Architecture Today and Tomorrow:(re) Defining the Field. Intellect Books, 2022.

Hasan, Muhammad Ismail., Bintang Noor Prabowo, and Hazrina Haja Bava Mohidin. "An Architectural Review of Privacy Value in Traditional Indonesian Housings: Framework of Locality-Based on Islamic Architecture Design." Journal of Design and Built Environment 21, no. 1 (April 2021): 21-28. https://doi.org/10.22452/jdbe.

Haruna, Ibrahim Abdullahi. "Hausa Traditional Architecture." (August 2016).

Al Husban, Safa AM., Ahmad AS Al Husban, and Yamen Al Betawi. "The Impact of the Cultural Beliefs on Forming and Designing Spatial Organizations, Spaces Hierarchy, and Privacy of Detached Houses and Apartments in Jordan.” Space and Culture 24, no. 1 (August 2018): 66-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218791934

Hwaish, Akeel Noori Almulla. "Concept of the Islamic House: A Case Study of the Early Muslims House." In Proceedings of 4th IASTEM International Conference, (November 2015): 86-93.

Ismail Alice S. "The Influence of Islamic Political Ideology on the Design of State Mosques in West Malaysia (1957-2003)." PhD diss., Queensland University of Technology, 2008.

Koirala, Saurav. "Cultural Context in Architecture” International Journal of Architecture and Planning (September 2021): 23-27. https://doi.org/10.51483/IJARP.

Lodson, Joyce, John Emmanuel Ogbeba, and Ugochukwu Kenechi Elinwa. "A Lesson from Vernacular Architecture in Nigeria." Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 2, no. 1 (June 2018): 84-95. https://doi.org/10.25034/ijcua.2018.3664

Maina, J. J., A. A. Muhammad-Oumar, and H. T. Saad. "Harnessing African Architectural Traditions for Environmental Sustainability." Cent. Black Afr. Arts 104 (February 2018): 1-22.

Malik, Sana., and Beenish Mujahid. "Perception of House Design in Islam." Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 6, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 52-76. https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.62.01

Moughtin, J. C. "The Traditional Settlements of the Hausa People." The Town Planning Review 35, no. 1 (April 1964): 21-34.

Muhammad-Oumar, Abdulrazzaq Ahmad. “Gidaje: The Socio-Cultural Morphology of Hausa living Spaces.” PhD Dissertation, University of London, University College London, 1997.

Nafi, Dian. Islamic Architecture. Hasfa, 2023.

Noma, Tanimu Adamu Jatau., Ali F. Bakr, and Zeyad M. El Sayad. "Integration of Hausa Traditional Architecture in the Development of Abuja: A Methodological Approach." International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions 10, no. 1 (April 2022): 27-39. https://doi.org/10.37745/ijasct.2014.

Obi-Ani, Ngozika Anthonia., and Paul Obi-Ani. "Pan–Africanism and the Rising Ethnic Distrust in Nigeria: An assessment." Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 1, no. 1 (October 2019): 65-75.

Oladejo Mutiat Titilope. "Tradition of Concubine Holding in Hausa Society (Nigeria), 1900–1930." AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities 9, no. 1 (April 2020). https://doi.org/118-129. 10.4314/ijah.v9i1.12

Olotuah, Abiodun Olukayode, and Damilola Esther Olotuah. "Space and Cultural Development in Hausa Traditional Housing." International Journal of Engineering Sciences & Research Technology 5, no. 9 (September 2016): 654-59. https://doi.10.5281/zenodo.155089.

Omer Spahic. "Towards Understanding Islamic Architecture." Islamic Studies 47, no. 44 (Winter 2008): 483-510.

Oni-Jimoh, Temi., Champika Liyanage, Akanbi Oyebanji, and Michael Gerges. "Urbanization and Meeting the Need for Affordable Housing in Nigeria." Housing, Amjad Almusaed and Asaad Almssad, IntechOpen 7, no. 3 (November 2018): 73-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.78576.

Pragyan Dash, Shanta., and Deepika Shetty. "Cultural Identity in Sustainable Architecture." International Research Journal on Advanced Science Hub 2, no. 7 (July 2020): 155-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.47392/irjash.2020.81

Umar, Gali Kabir, Danjuma Abdu Yusuf, Abubakar Ahmed, and Abdullahi M. Usman. "The Practice of Hausa Traditional Architecture: Towards Conservation and Restoration of Spatial Morphology and Techniques." Scientific African 5 (September 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00142.

Salim, Bashir Umar., Ismail Said, Lee Yoke Lai, and Raja Nafida Raja Shahminan. "Driving Factors of Continuity for Kano Emir Palace towards Safeguarding its Cultural Heritage." Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences andHumanities 29, no. 3 (September 2021):1631-1650. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.3.09

Samir, H. Anna Klingmann, and Mady. Mohamed. "Examining the Potential Values of Vernacular Houses in the Asir Region of Saudi Arabia." Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II 177 (2018): 1127. https://doi:10.2495/IHA180031

Skinner, R. “Traditions, Paradigms and Basic Concepts in Islamic Psychology.” Journal of Religion and Health 58, (August 2019):1087-1094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0595-1.

Taher Tolou Del., Mohammad Sadegh, Bahram Saleh Sedghpour, and Sina Kamali Tabrizi. "The Semantic Conservation of Architectural Heritage: The Missing Values." Heritage Science no. 8 (July 2020): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00416-w

Prima, Eka Cahya. "The Role of Culture on Islamic Architecture." Islamic Research 4, no. 1 (April 2021): 30-34. https://doi.org/10.47076/jkpis.v4i1.42.

Zahedi Amiri, Nesa. "Socio-Cultural Challenges to Women’s Solo Domestic Travel Pursuits: A Mini-Ethnographic Case of Iranian Culture." Master diss., Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario, 2023).

Zhang, J., and Z. L. Yusuf. "A Study on the Building Materials and Construction Technology of Traditional Hausa Architecture in Nigeria." In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Materials, Chemistry and Engineering (2018): 434-41.

[1]Muhammad Alifuddin, Alhamuddin Alhamuddin, Rosadi Andri, and Amri Ulil, “Understanding Islamic Dialectics in the Relationship with Local Culture in Buton Architecture Design,” KARSA: Journal of Social and Islamic Culture 29, no.1 (June 6, 2021): 230–54, https://doi.org/10.19105/karsa.v29i1.3742

[2]Ali Saeed Bokhari, Tarek Mohamed Hammad Mahmoud, and Beggas Djamel, “Impact of Islamic Values and Concepts in Architecture: A Case Study of Islamic Communities,” Sustainable Development and Planning XI, (November, 2020): 383-396, https://doi.org/10.2495/sdp200311

[3]Rasjid Skinner, “Traditions, Paradigms and Basic Concepts in Islamic Psychology,” Journal of Religion and Health 58, (March 23, 2018): 1087-1094, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0595-1.

[4]Sana Malik, and Beenish Mujahid, “Perception of House Design in Islam: Experiences from Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan,” Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 6, no. 2 (February 10, 2019): 53–76, https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.62.04.

[5]Mohd Akil Muhamed Ali, Mohd Farhan Md Ariffin, Mohd Nazri Ahmad, and Shafiza Safie, "Islamic Values in The Design of Residential Internal Layout," International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 12, no.11 (November 10, 2022): 1728-1740, http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i11/15051.

[6]Nesa Amiri Zahedi, “Socio-Cultural Challenges to Women’s Solo Domestic Travel Pursuits: A Mini-Ethnographic Case of Iranian Culture,” (2023), http://hdl.handle.net/10464/17743.

[7]Muhammad Akhtar, Muhammad Atif Aslam Rao, and Kaplan Doğan, “Islamic Intellectualism Versus Modernity: Attempts to Formulate Coherent Counter Narrative,” Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 13, no.1 (May 5, 2023): 257-269, https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.131.18.

[8]Akeel Noori Almulla Hwaish, "Concept of The Islamic House; A Case Study of the Early Muslims House," In Proceedings of 4th IASTEM International Conference, (November 12, 2015): 86-93, https://doi.org/978-93-85832-36-9.

[9]Al-Baqara 2:233, 235, 236.

[10]Malik, “Perception of House Design in Islam,” 53–76.

[11]Ali, “Islamic Values in The Design,” 1728-1740,

[12]Majedh F. Alhuseini, Ghadah A. Altammam, Bashayer R. AlSehaimi, Donia M. Bettaieb, Abeer A. Alawad and Khawlah J. Tarim," Conceptual Inspiration from Heritage: The Design Philosophy Surrounding the Saudi Arabian Rowshan," City, Territory and Architecture 10, no. 1 (2023): 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-023-00204-6.

[13]Bokhari, “Impact of Islamic Values and Concepts in Architecture, 383-396.

[14]Al-Baqara 2:233, 235, 236.

[15]Mutiat Titilope Oladejo, “Tradition of Concubine Holding in Hausa Society (Nigeria), 1900-1930,” AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities 9, no.1 (April 28, 2020): 118-29, https://doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v9i1.12.

[16]Tanimu Adamu Jatau Noma, F. Bakr Ali, and M. El Sayad Zeyad, “Integration of Hausa Traditional Architecture in the Development of Abuja: A Methodological Approach,” International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions 10, no.1 (April 16, 2022):27-39, https://doi.org/10.37745/ijasct.2014/vol10no1pp.

[17]Sabrina Alice Ismail, “The Influence of Islamic Political Ideology on the Design of State Mosques in West Malaysia (1957-2003)” (PhD diss., Queensland University of Technology, April 1, 2009).

[18]Muhammad Ismail Hasan, Noor Prabowo Bintang, and Haja Bava Mohidin Hazrina, “An Architectural Review of Privacy Value in Traditional Indonesian Housings: Framework of Locality-Based on Islamic Architecture Design,” Journal of Design and Built Environment 21, no.1 (April 30, 2021): 21-28, https://doi.org/10.22452/jdbe.

[19]Spahic Omer, “Towards Understanding Islamic Architecture,” Islamic Studies 47, no.4 (2008): 483-510. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20839141.

[20]Malik, “Perception of House Design in Islam,” 53–76.

[21]Dian Nafi “Islamic Architecture,” Hasfa, (February 16, 2023), https://www.hasfa.co.id.

[22]Skinner, “Traditions, Paradigms and Basic Concepts in Islamic Psychology,” 1087-1094.

[23]Eka Cahya Prima, “The Role of Culture on Islamic Architecture,” Islamic Research 4, no. 1 (April 25, 2021): 30-34, https://doi.org/10.47076/jkpis.

[24]Zi-Mu Fan, Zhu Bo-Wei, Xiong Lei, Huang Sun-Weng, and Tzeng Gwo-Hshiung, “Urban Design Strategies Fostering Creative Workers' Sense of Identity in Creative and Cultural Districts in East Asia: An Integrated Knowledge-Driven Approach,” Cities 137, (June, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104269.

[25]Dash Shanta Pragyan, and Shetty Deepika, “Cultural Identity in Sustainable Architecture,” International Research Journal on Advanced Science Hub 2, no. 7 (July 28, 2020):155-158, https://doi.org/10.47392/irjash.2020.81.

[26]Saurav Koirala, “Cultural Context in Architecture,” International Journal of Architecture and Planning 1, no. 2 (September 5, 2021): 23-27, https://doi.org/10.51483/IJARP.

[27]Avciarchitects, Innovation in Architecture the Concept,” Retrieved from (December 22, 2015), https://avciarchitects.com/en/innovation-in-architecture.

[28]Joy Joshua Maina, Abdulrazzaq Ahmad Muhammad-Oumar, and H. T. Saad, “Harnessing African Architectural Traditions for Environmental Sustainability,” (February 15, 2018): 1-22.

[29]Tolou Del Taher, Sadegh Mohammad, Saleh Sedghpour Bahram, and Kamali Tabrizi Sina, “The Semantic Conservation of Architectural Heritage: The Missing Values,” Heritage Science, (July 14, 2020): 70, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00416-w.

[30]Haitham Samir, Klingmann Anna, and Mohamed Mady, “Examining the Potential Values of Vernacular Houses in the Asir Region of Saudi Arabia,” Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II, no. 27, (2018) https://doi.org/10.2495/IHA180031.

[31]Ali, “Islamic Values in The Design,” 1728-1740.

[32]Noori “Concept of The Islamic House,” 86-93.

[32]Al-Baqara 2:233, 235, 236.

[33]Nafi, “Islamic Architecture,” (2023).

[34]Taher, “The Semantic Conservation of Architectural Heritage,” 70.

[35]Noori “Concept of The Islamic House,” 86-93.

[36]Hamza Babangida, and Halima Sani-Katsina, “Integrating Islamic Design Principles for Achieving Family Privacy in Residential Architecture,” Journal of Islamic Architecture 5, no.1 (Jun, 2018):9-19.

[37]Sana Malik, “Perception of House Design in Islam,” 53–76.

[38]Muhammad Ismail Hasan, Noor Prabowo Bintang, and Hazrina Haja Bava Mohidin, “An Architectural Review of Privacy Value in Traditional Indonesian Housings: Framework of Locality-Based on Islamic Architecture Design,” Journal of Design and Built Environment 21, no. 1 (Apr 30, 2021): 21-28, https://doi.org/10.22452/jdbe.

[39]Antoni S. Folkers, Belinda A. C. van Buiten, Modern Architecture in Africa: Practical Encounters with Intricate African Modernity (Springer 2019), 9-19.

[40]Samir, “Examining the Potential Values,” 27.

[41]al-Nur, 24:28.

[42]Ismail, “The Influence of Islamic Political Ideology,” (2009).

[43]Ibid.

[44]Hasan, “An Architectural Review of Privacy Value,” 21-28.

[45]Samir, “Examining the Potential Values,” 27.

[46]Noori, “Concept of The Islamic House,” 86-93.

[47]Nafi, “Islamic Architecture,” (2023).

[48]Skinner, “Traditions, Paradigms and Basic Concepts,” 1087-1094.

[49]Mohammad Gharipour, and E. Coslett Daniel eds, Islamic Architecture Today and Tomorrow:(re) defining the Field (Intellect Books, 2022), 107-118.

[50]Samir, “Examining the Potential Values,” 27.

[51]Taher, “The Semantic Conservation of Architectural Heritage,” 70.

[52]Reda Ibrahim Ibrahim Elsayed Abdelgalil, “The Philosophy of Creativity, Innovation, and Technology from an Islamic Perspective,” Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 13, no. 1(May 26, 2023):228-24 https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.131.16.

[53]Mario Bunge, and Abd al-Rahman Taha, Modernity and the Ideals of Arab-Islamic and Western-Scientific Philosophy, (Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2022), 51-83.

[54]Ngozika Anthonia Obi-Ani, Paul Obi-Ani, “Pan -Africanism and the Rising Ethnic Distrust in Nigeria: An assessment” Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 1 no. 1 (October, 10 2019): 65-75.

[55]Temi Champika Liyanage Oni-Jimoh, Oyebanji Akanbi, and Gerges Michael, “Urbanization and Meeting the Need for Affordable Housing in Nigeria,” Housing, Amjad Almusaed and Asaad Almssad, Intech Open 7, no. 3 (November 28, 2018):73-91, http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.78576.

[56]Nafi, “Islamic Architecture,” (2023).

[57]Omer, “Towards Understanding Islamic Architecture,” 483-510.

[58]Gali Kabir Umar, Abdu Yusuf Danjuma, Ahmed Abubakar, and Muhammad. Usman Abdullahi. "The Practice of Hausa Traditional Architecture: Towards Conservation and Restoration of Spatial Morphology and Techniques,” Scientific African, (September 2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00142.

[59]Folahan Anthony Adenaike, Pearl Opoko Akunnaya and Kolawole G. K Oladunjoye, “A Documentation Review of Yoruba Indigenous Architectural Morphology,” International Journal of African and Asian Studies 66, no.1 (July 31, 2020):27-31, https://doi.org/10.7176/JAAS/66-05.

[60]O. Bello, and B. Jolaoso. Character-Extinction of Yoruba architecture: “An Overview of Facades of Residential Buildings in South-Western,” Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies 8, no.3 (June 1, 2017):143-150, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-b391bd047.

[61]Emmanuel Arenibafo Femi, “The Transformation of Aesthetics in Architecture from Traditional to Modern Architecture: A case study of the Yoruba (Southwestern) region of Nigeria,” Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 1, no.1 (January 2, 2017):35-44, https://doi.org/10.25034/1761.1(1)35-44.

[62]Babatunde E. Jaiyeoba, Abimbola O. Asojo and Bayo Amole, "The Yoruba Vernacular as A Paradigm for Low-Income Housing: Lessons from Ogbere, Ibadan,” International Journal of Architectural Research, (March, 2017): 101-118.

[63]Mohammed Aliyu, Hussaini Haruna, “Architectural Revivalism: The Progressive Design Approach in Hausa Communities,” International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications, (December 24, 2021): 143-149, https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijaaa.20210704.16.

[64]Z. R. Dmochowski, An Introduction to Nigerian Architecture-Northern (London: Ethnographica, 1990):1-2.

[65]Isa Ibrahim Danja, Xue Li, and S.G. Dalib, “Vernacular Architecture of Northern Nigeria in the Light of Sustainability,” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, (May 9, 2017):22-24, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/63/1/012034.

[66]Aliyu, “Architectural Revivalism,” 143-149.

[67]Abdulqadir Bello, and István Egresi, “Housing Conditions in Kano, Nigeria: A Qualitative Assessment of Adequacy,” Analele Universitatii din Oradea, Seria Geografie 2, (December 2, 2017): 205-229, http://istgeorelint.uoradea.ro/Reviste/Anale/anale.htm.

[68]Adenaike, “A Documentation Review of Yoruba,” 27-31.

[69]J Moughtin, “The Traditional Settlements of the Hausa People,” The Town Planning Review 35, no. 1 (April 1964):21-34, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40102417.

[70]Abiodun Olukayode Olotuah, and Esther Olotuah Damilola, “Space and Cultural Development in Hausa Traditional Housing,” International Journal of Engineering Sciences 5, no. 9 (September 2016):654-659, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.155089.

[71]Tanimu Adamu Jatau Noma, Ali F. Bakr, and Zeyad M. El Sayad, “Integration of Hausa Traditional Architecture in the Development of Abuja: A Methodological Approach,” International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions 10, no. 1 (April 16, 2022):27-39, https://tudr.org/id/eprint/391.

[72]Joyce Lodson, Emmanuel Ogbeba John, and Kenechi Elinwa Ugochukwu, "A Lesson from Vernacular Architecture in Nigeria," Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 2, no. 1 (June 1, 2018): 84-95, https://doi.org/10.25034/ijcua.2018.3664.

[73]Anthonia, “Pan -Africanism and the Rising Ethnic,” 65-75.

[74]Mohammed Aliyu, Ahmad Jafar Ahmad, “Questioning the Neo-Classical Residential Buildings of Kano Metropolitan City Within the Context of Hausa Traditional Architecture,” Journal of Advanced Research in Construction and Urban Architecture 4 no. 3 (December 24, 2021): 38-47.

[75]Safa AM Al Husban, AS Al Husban Ahmad, and Al Betawi Yamen, “The Impact of the Cultural Beliefs on Forming and Designing Spatial Organizations, Spaces Hierarchy, and Privacy of Detached Houses and Apartments in Jordan,” Space and Culture 24, no.1 (August 6, 2018):66-82, https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218791934.

[76]Aliyu Maiwada Danjuma et al, “Examination of Hausa Cultural Identity in Architectural Design,” PalArch's Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17, no.9 (December 25, 2020):10122-10133, https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/6371

[77]Bilkisu Mukhtar T, U. Mandi Abubakar, F. Muhammad Umar, and Fatima Binta Yahaya, “The Influence of Modernism on Hausa Residential Architecture: Case Study of Kano Metropolis,” Journal of Engineering, Computational and Applied Sciences 4, no.02 (June 15, 2020).

[78]Ibrahim Abdullahi Haruna, “Hausa Traditional Architecture,” (August 11, 2016).

[79]Adamu, “Integration of Hausa Traditional,” 27-39.

[80]Mohammed Aliyu, “Architectural Revivalism,” 143-149.

[81]Anthonia, “Pan -Africanism and the Rising Ethnic,” 65-75.

[82]Olotuah, “Space and Cultural Development,” 654-659.

[83]Anthonia, “Pan -Africanism and the Rising Ethnic,” 65-75.

[84]Arenibafo Femi, “The Transformation of Aesthetics,” 35-44.

[85]Hasan, “An Architectural Review of Privacy Value,” 21-28.

[86]Aisha Abdulkarim Aliyu, Sagir Abdullahi, Sabrina Alice Ismail, and Aminu Dodo Yakubu, “Considering Afrocentrism in Hausa Traditional Architecture,” International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, (November 11, 2022):52-57, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7325456.

[87]J Zhang J and Z L Yusuf, “A Study on the Building Materials and Construction Technology of Traditional Hausa Architecture in Nigeria,” In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Materials, Chemistry and Engineering, (2018): 434-441.

[88]Anthonia, “Pan -Africanism and the Rising Ethnic,” 65-75.

[89]Bashir Umar Salim, Said Ismail, Yoke Lai Lee, and Nafida Raja Shahmina Raja, “Driving Factors of Continuity for Kano Emir Palace towards Safeguarding its Cultural Heritage,” Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities 29, no.3 (September 15, 2021):1631-1650, https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.3.09.

[90]Abdulrazzaq Ahmad Muhammad-Oumar, “Gidaje: The Socio-Cultural Morphology of Hausa living Spaces,” (PhD diss., University of London, University College London, 1997), 23-26.

[91]Olotuah, “Space and Cultural Development,” 654-659.

[92]Danjuma et al, “Examination of Hausa,” 10122-10133.

[93]Oluwagbemiga Paul Agboola and Sule Zango Modi, “Development of Traditional Architecture in Nigeria: A Case Study of Hausa House Form,” International Journal of African Society Cultures and Traditions 1, no.1 (June 2014): 61-74.

[94]Anthonia, “Pan -Africanism and the Rising Ethnic,” 65-75.

[95]Bello, “Housing Conditions in Kano,” 205-229.

[96]Faisal Koko Auwalu, “Exploring the Different Vernacular Architecture in Nigeria,” International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions 7, no.1 (February 2019):1-12.

[97]Amina Batagarawa, and Rukayya Bashiru Tukur, Hausa Traditional Architecture in Sustainable Vernacular Architecture (Springer, ChamMarch, 2019), 207-227.